Reading Stuart Hall for the Climate Crisis

Stuart Hall’s politics of culture offers the left a blueprint for confronting the climate crisis.

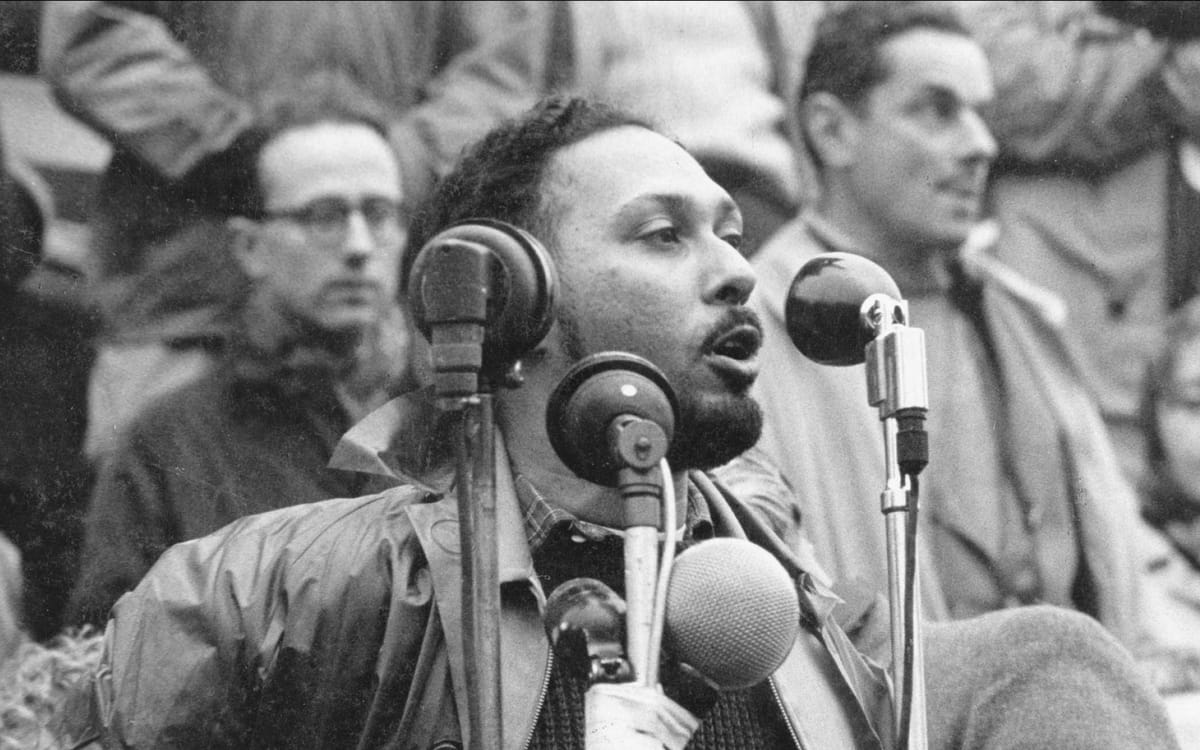

Stuart Hall is usually remembered as an analyst of popular culture and for his writings on Thatcherism, race and ethnicity. He was also, and perhaps primarily, a strategist, a cartographer of rough political terrain—someone who wanted to know how the powerful hold on to power and how working people might take it from them. A leading figure of the British New Left in the 1960s and 1970s, Hall belonged to a cohort of thinkers who sought a “Marxism without guarantees.” This would be a Marxism that eschewed the reductive economism of certain positions deemed “orthodox”. It would also pay close attention to culture—people’s shared social practices as well as their systems for making sense of the world—in both reproducing and challenging an unequal social order. Above all, it would be a strategic Marxism, designed to aid real movements for socialism rather than merely lament capitalism’s tenacity or prophesy its inevitable implosion.

Hall wrote very little about the environment; environmental issues were, until quite recently, considered by many on the left to be middle-class concerns, distractions from the real political struggles happening on the shop floor or in the streets of overpoliced cities. Edward Said famously described environmentalism as “the indulgence of spoiled tree-huggers”, while Hall himself commented on environmentalism’s often “personalized and apolitical form.” But the insights developed over his career, which would take him from Kingston, Jamaica to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, then the University of Birmingham and eventually to the Open University, remain extraordinarily useful for anyone interested in a left politics that has something to say about today’s ecological crises.

Of the many concepts Hall refined, three are particularly germane to such a politics: conjunctural analysis, ideology and hegemony. Each reflected in some sense Hall’s frustration with shallow readings of Marx. While affirming the analytical power of Marx’s historical materialism, which put paid to the notion that ideas change the world on their own, Hall chafed at the brute mechanicism of Marxism’s popular variants, which treated ideas as simple reflections of one’s class position and portrayed history as a Rube-Goldberg machine clattering inexorably towards a workers’ utopia. People experience “class” and “history” obliquely, through many layers of mediation: through laws that set maximum hours and minimum wages, for example, or the ethics that valorize hard work, or social positions, like race or gender, that affect how or whether one works at all.

Influenced by the Trinidadian Marxist C.L.R. James as well as by Antonio Gramsci, Hall sought to devise a Marxism that took these political, social and cultural forces seriously, and which in doing so could address key questions of his post-war moment: why had capitalism not yet run aground on its own contradictions? Why did so many working people seem to accept a subordinate position in society? And, perhaps most importantly, what would it take to change this?